Houses of History:

These Walls Talk with a Purpose and a Plan

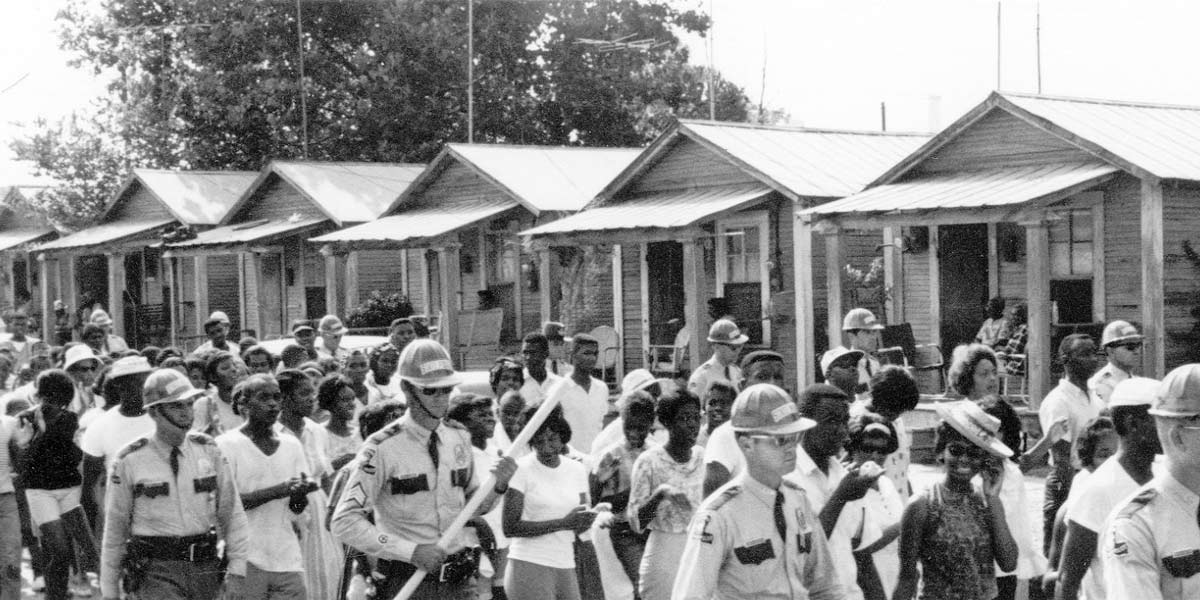

Bogalusa is home to both the Hicks House and the 1906 Mill House, two modest homes rich in history. Both are currently being turned into museums, dedicated to keeping the history, and the dreams, alive.

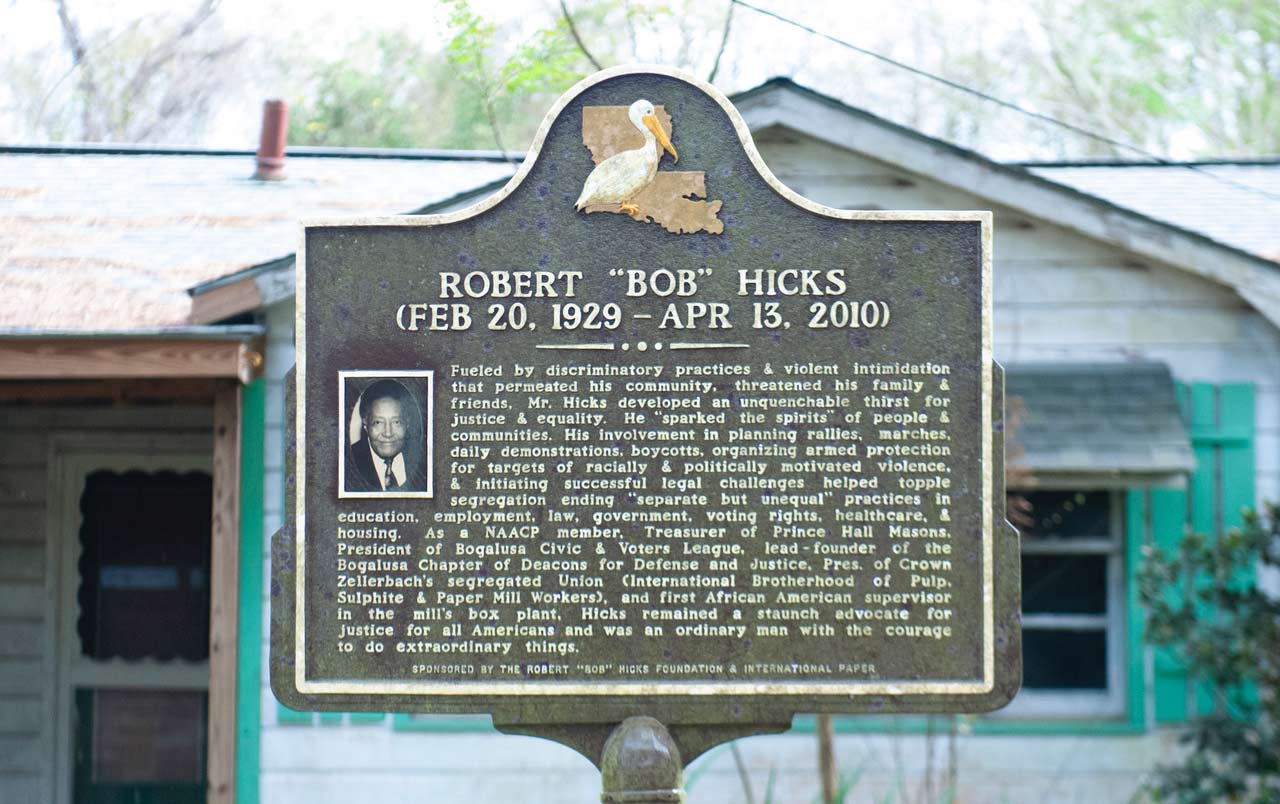

The Hicks House

When Robert and Valeira Hicks built their house on East 9th Street in Bogalusa, they had no idea that one day that home would be listed for significance on the National Register of Historic Places, and that East 9th would one day be renamed Robert “Bob” Hicks Street. Their family grew up in this house and so did Bogalusa’s Civil Rights Movement. Along with a loving home, this house served several purposes over the years. It was a safe haven, a medical triage station, a meeting place and base of operations for civil rights activities and, most famously, the birthplace of the Bogalusa chapter of the Deacons for Defense and Justice.

A Knock at the Door Ignites a Movement

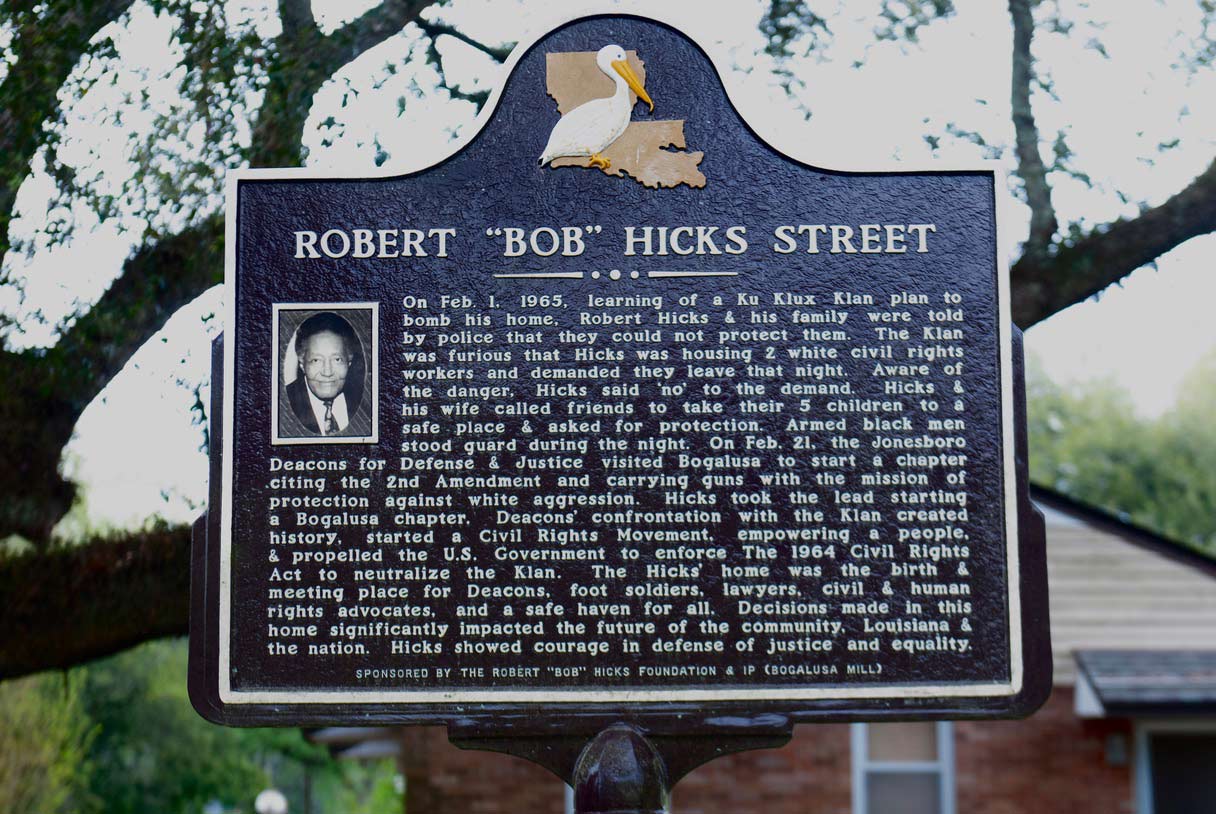

The Hicks House entered the history books on the night of February 1, 1965, when Robert and Valeira Hicks had invited three two guests into their home–Steve Miller and Bill Yates, two white CORE workers whose lives would have been at risk at any nearby hotel.

Late that night, there was a knock at the door. Deputy Sheriff Claxton Knight and Police Chief Doyle Holliday had come to tell Hicks a mob of 200 white men had gathered nearby. If Hicks didn’t put the white activists out, he said, the mob would burn the house down and murder everyone in it. The sheriff made it clear not to expect help from law enforcement: “We have better things to do than protect people who aren’t wanted here.”

Valeira Hicks turned to her husband and said, “This is some mother’s child, and they’re going to do to them just like they did to those kids in Philadelphia. Bob, don’t let them take them.” She was referring to James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, the three civil rights workers who had been murdered months earlier at the hands of the Ku Klux Klan and local law enforcement in Philadelphia, MS. Robert Hicks did not hesitate. When Yates asked if they could stay, he simply replied, “Hell, yeah, you’re a guest in my house.” He later recalled, “We just knew that if [they] left our house, we would never see them alive again.”

The Hicks family went into action, phoning black men from all over Bogalusa–fellow mill workers, church brethren, even patrons at a late-night dance at the American Legion Hall–asking them to get to the house as quickly as possible, to bring a gun, and to call another man and pass on the message. Once the calls were made, a car pulled up to the back of the house and the Hicks children were ushered to safety. Within minutes, black men with shotguns began arriving from all directions. They stationed themselves around the house, on the roof, even perched on trees.The sheriff, who had remained parked outside, drove off. The angry mob never appeared.

The events of that night marked a point of no return for Robert Hicks and the men who had come to defend the house. From that moment, they were committed to building the Bogalusa Civil Rights Movement, a movement that was unique at the time because it broke from the principles of non-violence espoused by Martin Luther King and other civil rights leaders, and instead asserted the right to armed self-defense against white aggression. For Hicks, “Since we can’t get the local officials to protect us, let’s back up on the Constitution and say that we can bear arms. We have a right to defend ourselves since the legally designated authorities won’t do it.”

The Deacons for Defense and Justice

Not far from Bogalusa, a self-defense organization of black men had recently formed in Jonesboro, Louisiana, to protect black citizens and civil rights workers from intimidation and attacks from the Ku Klux Klan and law enforcement. . It was called the Deacons for Defense and Justice. Less than a month after the sheriff’s visit, Bogalusa founded its own chapter of the Deacons, headquartered in Robert Hicks’ home and made up of many of the same men who had come forward with their guns that February night.

Hicks converted his breakfast room into a radio communications base, a necessity because the city not only monitored his calls, operators periodically shut off his phone lines. His daughter Barbara Hicks Collins remembers that the calls never stopped, broadcast loudly throughout the house. When a call for help came in, whoever was manning the radio would send out an encrypted alert and the Deacons would assemble to protect and defend.

A Base of Operations

The civil rights activity in the house was not limited to the Deacons. It continued to serve as a safe haven for civil rights workers and local citizens under threat from the KKK. It also served as a medical triage station for injured activists denied service at local hospitals. What’s more, it became the meeting place for the executive directors of the Bogalusa Civic and Voters League, and local headquarters to the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and other organizations, CORE. Civil rights attorneys from the black-owned New Orleans firm of Collins, Douglas and Ellie, and Richard Sobol of the Lawyers’ Constitutional Defense Committee commandeered the living room to take depositions and prepare several groundbreaking federal lawsuits.

All the while, the house remained a loving family home where Robert and Valeira Hicks raised their six children, Charles, Barbara, Robert, Gregory, Valeria, and their adopted son Darryl.

From 1965-1969, the Hicks House was guarded day and night by the Deacons for Defense and Justice. In 2014, the Hicks House and the 1906 Mill House next door to it were listed for significance on the National Register of Historic Places.

Today, the Robert “Bob” Hicks Foundation is rehabilitating the houses to historic preservation status so that they can become a museum and cultural center honoring the legacy of the heroes of the Bogalusa and Washington Parish Civil Rights Movement.

The 1906 Mill House

The 1906 Mill House

The 1906 Mill House dates back to Bogalusa’s earliest years as a company town, where employees of the sawmill lived as de facto dependents of the Great Southern Lumber Company. The company “owned virtually every board and nail in the place,” from homes and shops to the hospital and utility companies. Even the city’s name was trademarked. Bogalusa neighborhoods were rigidly segregated by race, ethnicity, and economic status. The Mill House was originally located in Bogalusa’s “colored quarters” where houses were smaller and lacked running water, bathrooms and fireplaces.

In the early 1950s, the Crown Zellerbach Corporation, which now owned the paper mill, began selling off the company houses. Robert Hicks bought the Mill House and moved it to his property on East 9th Street (now renamed Robert “Bob” Hicks Street). Robert and Valeira Hicks and their five children lived in the three-room shotgun with no bathroom, just an outhouse and a water faucet on the porch.

When Robert Hicks was able to build the larger house next door, Valeira Hicks’ aunt, Fannie Payton, moved into the Mill House. Born in 1886, Aunt Fannie worked as a domestic for white families who gave her the nickname “Mammie,” and she learned to speak of white people in a whisper. But when her family was threatened with violence, Aunt Fannie readily agreed to let her home be used as a safe haven and secondary medical triage center for civil rights workers, a communications center and a refuge for the Hicks children and the children of the Deacons for Defense and Justice, who were provided a safe and nurturing place to find some semblance of normality in a turbulent time. In 1965, Fannie Payton became the plaintiff in a successful desegregation lawsuit against the St. Tammany-Washington Parish Hospital and became the first black patient to share a hospital room with a white patient. Aunt Fannie died in 1990 at the age of 104. She was the oldest member of the Bogalusa Movement and an unsung hero of the struggle for equality and justice.

Schedule your visit

While the houses are not yet open to the general public, visitors are welcome. To schedule a tour for yourself or your group, please contact Barbara Hicks-Collins, foundation director, at (504) 237-4656 or [email protected]

Your Support Matters

With your help, we can create the Bogalusa Civil Rights Museum and keep the legacy alive